Located in the South-of-Market district (SOMA) of San Francisco this micro-school of 33 middle schoolers is a few blocks away from Yerba Buena (see Part 2). I spent a morning there speaking with the Head of School, Emily Dahm (who also is in charge of Yerba Buena), observing two lessons taught by "core educators" James Earle (social studies/English) and Eman Haggag (science), and interviewing Katie Berk, a product manager, from the technical side of the "micro-school."

Facing busy Folsom Street, AltSchool space is divided into four large carpeted rooms two of which were used that morning for lessons (no class I observed was larger than 15). The other two spaces include a room with desktop computers and commons area for the entire school to meet. Software engineers and staff (coders, designers, and product managers) were located in a large space in the back of the building adjacent to the classrooms and commons area.

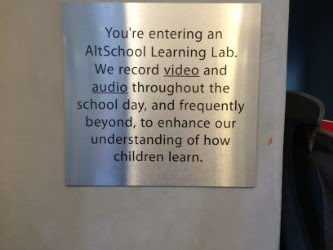

Each classroom space has wall-mounted cameras and microphones hanging from the ceiling--called Altvideo--that produce data for teachers to view later privately about the lesson they taught. The technical staff has produced an app that teachers can use to find the precise part of the lesson they want to see. This self-evaluation occurs during the school day and other times.

On November 7, 2016 I arrived at 8:00 AM and interviewed the Head of School and both core educators. School began at 9:00 with a "morning meeting." There were 21 twelve to fourteen year-olds sitting in a circle with Eman Haggag counting down from 10 to 0 to secure quiet for the "morning meeting" to begin. On a whiteboard are listed announcements:

Good Morning,

How are you? I am quite marvelous. Cupa' tea?

Few things:

--Feynman bring phones to class powered off (students are in different groups--(the internationally known physicist

Richard Feynman)--is name of one group of students)

--Field trip Wednesday--Altschool shirts + pencil + paper

--Ceramics class 11/17, 11/18/,11/22

Students ask logistics questions about upcoming field trip, teachers answer their questions.These morning meetings are to inform students of daily activities and build bonds of community among both students and adults.

At 9:10, students go to the Earle's and Haggag's spaces. I go to observe a 90-minute lesson in James Earle's room.

________________________________________________

*The camera is a red dot in a small square below "Join or Die" poster; the mics are in the ring suspended from the ceiling.

______________________________________________

There are 14 students in Earle's class, one with desks and chairs along the windows and walls facing the center. The students sit on the desks with their backs to windows and walls and their feet on the chairs.They appear used to the informality of the seating arrangements and easily shift to sitting at their desks later in the lesson.

In his third year at SOMA, Earle taught global cultures using art, literature, history, and science for eight years at a private school in East Hampton (NY). There he used digital tools extensively. He was attracted to AltSchool for its "public mission, inclusivity, and freedom to work on an integrated curriculum." *

Earle, wearing a checked long-sleeved shirt with a loosened gray tie over jeans, stands in the center of the room ready to launch the lesson on students writing their position papers on the struggle between colonists and Britain over trade, taxes, and loyalty to the Crown.

To pairs of students, he has assigned actual characters who lived in the years before the American Revolution when colonials were divided among themselves as patriots who sought representation in Parliament and loyalists to the Crown (e.g. British commander Jeffrey Amherst, Admiral Samuel Hood, colonist William Franklin). King George III and British Parliament were also divided over how to best treat the uppity colonists who didn't want to pay taxes that would recoup British costs in defending the colonies in an earlier French and Indian War that had lasted seven years.

Students have researched the person about whom they are expected to write a position paper. Earle had created playlists of sources, video clips, and readings located on students' Chromebooks covering these years and different individuals he had assigned to pairs of students. Some members of the class are just beginning to get a sense of their character's personality; others are at sea and today's lesson is aimed at answering students questions and get them to dig into the writing.

Earle stresses the importance of students knowing their character's personality and what positions the person would take on trade with Britain and colonists' representation in Parliament. He goes over the slide listing instructions on writing a position paper, paragraph by paragraph, and the importance of the students writing an internally consistent paper that reflects who their character is, their personality, and what stands that the person would take in this on-going struggle with the mother country.

After going over the parts of the position paper, Earle then says "Let's go around and ask questions." There are many.

One student asks about William Franklin, a colonial Loyalist (and son of Ben) and his personality that she gleaned from sources she used. Earle responds about how to develop a plan consistent with the character each team is going to write about. Knowing their character's views on trade, for example, become part of the position paper. Another student asks about her character who is a British soldier and how he would address his commander.

Earle interrupts the class for a moment as he sees six students who have opened their Chromebooks and have begun tapping away. He asks them to close their lids for now since the questions others ask can apply to their work. They do.

Students resume their questions. One asks whether they will work on the Island simulation (lessons that Earle created to show students the different factions in the colonies; the simulation has six islands with different resources where competition and cooperation do exist but change over time. An upcoming debate among the Islands will occur). Earle says they will have the debate. He turns to another student question.

After another few minutes of questions, Earle asks students to now sit at the desks so he can see what they are working on as they begin writing. All of the students either open their Chromebooks to read and re-read sources in their playlists or begin writing. Some students have their partners in the room and some are in the other class with Eman Haggag and even others are at Yerba Buena.

I speak to three students near me and ask what they are doing. One shows me the playlist she has and the video she is watching; another explains to me about the British soldier she is going to write about. One student has William Petty, the Earl of Shelburne, and wonders how to address and write a letter as a member of the House of Lords.

Earle goes to each student, listens to what the student is concerned about in the position paper or character he or she has been assigned, and has a mini-conversation before moving on to another student. To one student, he says, "get your fingers moving on the keyboard." The student does. For the remaining time in the lesson, students are figuring out their character's positions on different issues roiling colonist-British relations and at various stages of writing their position paper.

I leave the room and walk a few steps to the open space where Eman Haggag's science lesson on "Speed Machines"is underway. Part of the lesson is a lab measuring the speed of a marble going down a ramp. The open space is furnished with a series of black-topped lab tables (resistant to stains and flaking) holding three to four students facing the front of the space where there is an interactive white board that shows slides for the lesson.

Haggag came to SOMA this school year. She has taught eight years in charter and private schools in the Washington, D.C. area. In those different schools she had one laptop per students, interactive white boards and a host of digital tools available to her. What attracted her to AltSchool was the concept of experimenting in a "lab school" where different ideas about schools and classroom lessons can be tested. "Here," she says is the "autonomy I have sought in teaching." Moreover, she says: "I feel ownership of what I do. In this lab setting, I can practice what I preach."

By the time I enter the room, Haggag--wearing an ankle-length black skirt with a flowered blouse over a long-sleeved shirt and a blue scarf---has organized the 13 students into groups of three and four students collecting data on how fast a marble rolls down a ramp. Like Galileo rolling balls down an incline and measuring their speed, this lab sought to apply the formula:

SPEED =DISTANCE (DIVIDED BY) TIME

Students had already constructed an inclined plane out of 2' X 3' pieces of hard cardboard and scotch-taped a yard stick, marked off in 3" segments. The task for each group is to time how long the marble takes to go from the first segment to the second and then from the second until the next all the way to the 10th and last segment. Each student in the group has a task. One uses her smart phone as a stop-watch; another catches the marble at each segment and another records time and length of drop.

As I walk around the room, these 12 to 14 year-olds are engaged in the doing each step of the experiment and recording the data. Haggag walks to each group, inquires if there are any problems, and answers questions. At one point she says to the class: "You're getting into the groove. That's awesome."

I overhear one student--the marble catcher in a nearby group say to her group -mates: "This is really stressful."

Haggag asks students to begin looking at the data they have collected and enter it into a Data Table with columns for distance in centimeters (each segment of the yardstick), time, and speed. They are to calculate the speed of the marble for each segment by dividing the distance by the time it took to traverse the distance. Students enter data and have many questions. Some are answered by group members and friends in other groups; others by the teacher who goes to each group and checks on the data they entered. A few students say out loud the mistakes they made in setting up the experiment and executing it.

With about 20 minutes left to the lesson, Haggag stands on a chair with a four foot high "rain stick" that has small pebbles in it. She turns "the rain stick" upside down and the sound of the pebbles falling inside the stick is a sign that the teacher wants students' attention. The class quiets down. She then gives students instructions to disassemble cardboards, yardstick, and scotch tape, clean up any debris on floor and reassemble at their lab tables.

The students scurry about, clean up, and sit in their groups at each table.

Haggag then asks the whole group to think about what they learned from the experiment. Some students said that they did too many trials using the marble; others said they didn't do enough trials. One student said how hard it was to release the marble and get an exact time. In each instance the teacher asked what the student had learned from their mistakes. Carrying off an experiment, one student said, depends on how well a procedure is done. Done poorly, he said, then the data are wrong. Haggag compliments students for their candor in enumerating their mistakes.

The teacher now asks students to calculate the data they collected. Students talk among themselves as they enter the numbers in the Data Table.

After about five minutes, Haggag asks the class to review the data and think about the hypothesis they had from previous lessons and how certain many members of the class were then that "numbers never lie." She then goes over the estimates of speed that groups had calculated and how much variation existed among the groups using similar ramps, yardsticks, and marbles.

Even with these varying estimates, Haggag wants each group of students to graph the curve of the marble's speed that they recorded. She demonstrates on a slide how to put the various points on the grid--one axis is time and the other axis is distance--by counting the little blocks and where to insert a dot that with other dots will eventually produce a curve. She tells students that graph will show the "Speed of a Marble."

Students work on this in groups as I leave the lesson to have an interview with Katie Berk, a product manager on the technical side of the AltSchool. The technical staff are lodged on the same floor in a large space at the back of the building.

Of nearly 160 employees in the network of "micro-schools" in San Francisco, there are more than 70 educators and about 30 are on the technical staff (they are not teachers) working on products, as coders, designers, and product managers. I interviewed Berk. In her third year at AltSchool, she was previously a Lead Product Manager at Zynga where she led a team that produced games.

At AltSchool, the technology side of the school receives a gigantic flow of data from "network" schools, digests the information, and designs software that solve problems that teachers and students have with current platform and programs while coming up with different ways to help teachers make their work both easier and efficient to reach the goals teachers have set for their students.

Berk tells me that the main job of the technology side is to help teachers teach and students learn more efficiently. They accomplish this, she says, by having close contact with what both teachers and students are doing by having engineers and designers spend time every week watching teachers teach and talking with them..

Teachers, Berk told me, run into problems with certain aspects of the platform used across AltSchool and they want simple ways to do an "end-around" the problem. Also teachers have ideas on what can make lessons, say, in science or math, easier for students to grasp and have an idea that can turn into an item on a playlist or the designer can wrestle with what the teacher wants and figure out a solution that she and her colleagues can create for the teacher. This collaboration between teachers and technical staff at AltSchool was one of the reasons that Berk came to the "network" of "micro-schools." I thanked her for the time she spent with me and left.

_________________________

As I drive home after my interview with Berk, I think how unusual this partnership between educators and the technologist side of a school really is. On-site, skilled technical staff that confer frequently with their "users" to come up with solutions to teaching and learning problems while, at the same time, smart, experienced teachers can turn to designers and engineers to try out software ideas that teachers believe might help them teach and students learn is uniquely innovative. That partnership is uncommon in schooling today, both public and private.

Yes, I thought, there are issues of privacy for both teachers and students amid constant surveillance during school hours that still need to be negotiated. Firewalls to prevent hacking or sharing information have to be strong enough not to be breached. That issue will not disappear.

Another thought occurred to me as I drove south on the freeway. AltSchool was practicing a form of progressive pedagogy that would have had John Dewey nodding in agreement. Yet, at the same time, AltSchool had married their progressive ways of teaching and learning to the sought-after classroom and organizational efficiencies that new technologies provide in the "micro-school" network. Maybe

Edward Thorndike, that early 20th century "educational engineer" who thought everything could be measured and analyzing data would point the way to better managed and efficient schools would, along with John Dewey, be nodding in agreement for the first time (see

here). Bringing together these two wings of the progressive movement a century ago finally into one network of schools can be done, reformers might conclude, albeit at $26K per student a year.

__________________

* In an interview prior to the lesson, Earle succinctly told me how digital tools at the Ross School where he taught previously and here at the AltSchool have helped him negotiate the inherently impossible task of "managing the complexity of teaching." He appreciates how many decisions, how many activities, how many student psyches come into play with his expertise and personality in a lesson. He seeks to have students acquire the skills and concepts he wants to communicate and have students not only grasp both but also come to understand and use in their school career. Negotiating this daily complexity of teaching is, according to Earle, aided, in part, by the digital tools he has available and uses with his students. Those tools are helpful to "manage the complexity of teaching," he says, but it is still a high mountain to climb every day.

39 COMMENTS

Tournachonadar

Illiana 4 minutes agoDr. John Burch

Mountain View, CA 8 minutes agoLaura

NJ 11 minutes agoYesterday while driving I heard Dvorak's "In Nature's Realm." It blew me away with its warmth, depth, and resonance. It sounded so alive.

Hearing it was ironic, as I'd heard a digital version (on an unrelated station) just a few days before while driving to Thanksgiving. It was pretty ho-hum.

You could attribute the difference to the conductor, orchestra, recording space, and other factors.

But the reality is, digital recording eliminates many of the overtones that give us richer harmonies and a fuller experience.

It's great analogy for personal vs. digital communications and friendships.

98% of communication is non-verbal. Digital friendships and communications are fine and have their place -- but we might all remember that they remove the overtones.

Life feels kinda flat without the real thing.

Thankfully, I have friends who feel the same way.

Lost in Space

Champaign, IL 12 minutes agoJenifer Wolf

New York 13 minutes agoredweather

Atlanta 13 minutes agoArt Work

new york, ny 14 minutes agoWho says you can't do both ?

Hanna

Richmond 15 minutes agoDennis

Johns Island, SC 16 minutes agoBart Grossman

Albany, CA 3 hours agoBob Garcia

Miami 6 hours agoAnd none of the debaters mentions the growing use of social media as a means for the police and spy agencies to conduct surveillance on the population.

Matayah Fox

Portland, OR 10 hours agoSara

Oakland Ca 10 hours agoOur brans develop in a complex experiential field of attachment, emotional valence, sights, smells and unconscious communication. Even the presence of Mirror Neurons indicate we are innately wired to feel real life and learn from it. It is essential nutrition.

On line 'relationships' are like processed food. They may be filling & easy, but they cause diabetes & obesity, omitting crucial nutrients. They also undermine organic farming & sustainable agriculture.

Tat is the analogy to cyber relational claims...it looks just like real human contact...but isn't hood for us.

sfdphd

is a trusted commenter San Francisco 11 hours agoWe should be acknowledging the problems and find ways to compensate for that as well as celebrate the good aspects.

John Smith

Cherry Hill NJ 11 hours agoPatricia Mueller

Parma, Ohio 11 hours agoMarkH

Delaware Valley 13 hours agoTo the extent that online communication becomes a starting point for knowing people face-to-face, I see it as a valuable asset.

To the extent that online communication displaces opportunities for knowing people face-to-face, I see it as a grievous loss.

Matt James

NYC 13 hours agoOne might say: "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way – in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only."

Matt D.

New York 13 hours agoAnne

Washington 14 hours agoHaving a couple of close Internet friends has helped. I'm not knocking friendships that don't involve personal contact. Sometimes, it's all there is.

Art Work

new york, ny 13 minutes agoWho says you can't do both ?

dmbones

Portland, Oregon 14 hours agoI'm invested in this question. I've devoted over a third of my adult life to a daily practice of yoga, meditation and chanting, seeking the fruits of our human biology. Yogic and transcendentalist myths reveal that our physical manifestation is a vehicle for our light body, or soul, to become manifest. This occurs when our capacity for observing closely the workings of our body leads to the realization that we are really more the observer than the object of our observations. In this evolved space, the words of Sri Aurobindo are understood, "We are consciousness, not life and form."

I found a video in my search after answers by the Dalai Lama in which he replies to an enquiry about a bio-technological future. He said, "I welcome the opportunity for my consciousness to be downloaded into a computer, or other form." With this statement, he supports the notion that we are more than our materiality, and that our materiality is simply a vehicle for our consciousness.

For those who have torn loose from the vales of self-discovery, ideation as consciousness is a state of being. In this state, one is both the individual observer and the whole of the object being observed, a holographic capacity that is both singular and collective, whether physically manifest or digital.

Andrew Peterson

Groton MA 14 hours agoSteveRR

CA 14 hours agoThis is the other problem with on-line saturation - you come to believe that just saying "stuff" - makes it true "stuff".

Your two examples are movements where people are actually enacting change not clicking for change and they depend on the real life activities of various people to actually - you know - do "stuff". You want slactivism - how about #bringourgirlshome?

I go college - I see this slacktivism every day - and trust me - it takes a great deal of self-control to avoid falling prey to "mocktivism".

Hannah Marazzi

Ottawa 14 hours agoSam

Siegel 14 minutes agoRoberto Fantechi

Florentine Hills 14 hours agoSaluti