The Hechinger Report, June 22, 2012

One company, Australian United States Services in Education—or AUSSIE—has dominated the New York City market in on-the-job teacher training for more than 10 years. And it’s a big market.

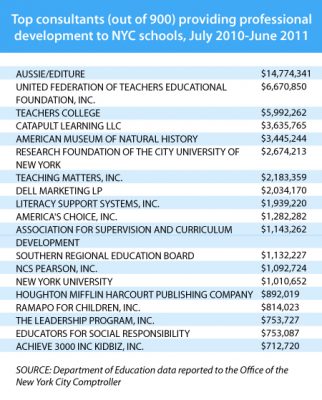

In total, city schools spent about $100 million on training for teachers and principals. The New York-based AUSSIE, which was recently acquired by an Australian company, Editure, took in more than $15 million of that amount last year, making it the system’s top provider of professional development, according to an analysis by The Hechinger Report of a decade’s worth of school spending data obtained from the city education department.

According to the records, dozens of schools spend more than $70,000 annually—at about $1,000 per day—on AUSSIE consultants, many imported from Australia.

“I was always very impressed with the amount of money that New York City was willing to put into professional learning,” said Diane Snowball, an Australian who co-founded AUSSIE with her husband in 1992. She is now retired and no longer involved with the company.

More than ever, principals are looking for ways to help teachers improve their skills as the state increases accountability. But though schools may have to prove they’re increasing student test scores, the city’s department of education doesn’t hold private companies to the same rules. There is little oversight of the money funneled to private consultants who provide training to teachers, or guidance to help principals figure out which ones help improve student achievement.

In one of its contracts with the city, AUSSIE cites growth on tests scores in two Bronx districts and three struggling schools where it has worked. But, as with most providers, there are no independent reviews of AUSSIE’s performance in terms of student test scores or other measures of school progress. (Company officials declined to comment for this story.)

AUSSIE has spread because it “provided strong coaching to schools,” said Josh Thomases, the department’s deputy chief academic officer, in a statement. Education department officials say they want principals to decide which providers work best for them.

“We’ve watched organizations that have not done as good a job as we would have hoped…or who are new on the scene that have done interesting and exciting work, and have shared that information around,” Thomases said. “What we’re not willing to do is take away principal discretion. We will support, inform and counsel, but professional development works best in the context of a principal’s clear vision.”

AUSSIE’s reputation is mainly built on anecdotal evidence, including a successful reform effort in the 1990s in District 2, which encompasses parts of Lower Manhattan, Chelsea, Greenwich Village and the Upper East Side.

Professional Development

The Hechinger Report is investigating how professional-development funds are spent in the country’s largest school system—New York City—as well as in other districts around the nation to see what we can learn from schools, districts and countries that excel at ongoing teacher training. This story is part of the ongoing series.READ MORE

Snowball was well known in Australia as a literacy expert, so in the early nineties the superintendent of District 2 invited her to train principals and teachers in Australian ideas about reading. “When I first came to New York, every kid was given the same book to read, whether they could read it or not, rather than putting something in their hands they could read,” Snowball said.

The so-called “balanced literacy approach” was supposed to go beyond simply teaching children how to read, to encourage them to actually enjoy it. The idea was well established in Australia, but was just catching on in the United States.

With the Australians’ help, District 2 began to thrive, and it now contains some of the highest-performing and most coveted public schools in the city. Snowball and her husband, Greg Snowball, founded AUSSIE, first focusing on reading and, later, math and other subjects.

Daria Rigney, a former superintendent and who is now a literacy consultant, was a school principal in District 2 at the time, and calls the AUSSIE consultants “consummate professionals.”

“They’d been principals. They’d been superintendents. So they had a very wide, deep knowledge of teachers, of communities of teachers, of supporting principals,” she said.

But the AUSSIE consultants were also supposed to be temporary. “The idea was not to hire AUSSIES forever and ever, and that they become this external wing of your organization,” Rigney said. “It was about building the capacity of the people who were the practitioners.”

The company was mostly concentrated in District 2 during the 1990s, but since then, AUSSIE consultants have spread from a few dozen schools and department of education programs to more than 300. In 2004, the company’s earnings from the system peaked at nearly $30 million, and at many schools, it has become a permanent fixture.

P.S. 279, a kindergarten-through-eighth grade school in the Bronx, has hired AUSSIE consultants nearly every year since 2004, spending a total of about $800,000, according to the analysis of the school spending data. Most of the school’s students are low-income minorities, and 40 percent of fourth-graders were proficient or better on state reading tests last year. But the school has received high marks from the city for its progress on student achievement.

On a recent morning, Olivia Atanasovska, speaking in a crisp Australian accent, was helping a group of P.S. 279 kindergarten teachers develop a curriculum for the following year. A teacher for 12 years in Melbourne and a literacy coach for three, Atanasovska is the youngest AUSSIE consultant at the company, she says. (There about 200 consultants total, many with more than 25 years of teaching experience.) It took half the year for teachers to trust her.

“It’s a question a lot of the teachers have asked, too: ‘Why an Australian?’ ” she said. “We’ve had our curriculum framework for a very long time, and we have been made accountable to work with this framework. So we understand our curriculum.”

Atanasovska works with several schools, most in the Bronx. During her weekly visits, she meets with administrators, teaches model lessons, observes classrooms and offers tips to teachers afterward, and facilitates meetings among teachers, like the kindergarten curriculum-writing session.

AUSSIE doesn’t focus on just reading anymore, but will customize its training to whatever a school principal wants. The consultants might help administrators sort through student test score data, or help teachers figure out how to incorporate new academic standards into their lessons.

AUSSIE doesn’t focus on just reading anymore, but will customize its training to whatever a school principal wants. The consultants might help administrators sort through student test score data, or help teachers figure out how to incorporate new academic standards into their lessons.Although research is scarce on what sorts of in-school training programs work best, Atanasovska’s work is similar to the sort of “job-embedded” help for teachers and schools that experts say shows the most promise.

The school has become reliant on AUSSIE for several reasons, says Principal James Waslawski. For one, teachers often leave his overcrowded, high-poverty school for jobs elsewhere, meaning each year he has a new crop of teachers who missed last year’s training. New approaches, such as a set of rigorous standards recently adopted by the state, also mean that his teachers and administrators need constant help figuring out how to adapt.

He used to rely on superintendents and other administrators within the school district to help him train his staff. That changed after former chancellor Joel Klein dismantled the old bureaucracy, Waslawski says. Consultants are “built into the model—they really are,” he says.

For the most part, Waslawski has had good experiences with consultants, but he wishes the department of education would provide more help for principals trying to navigate the growing teacher-training marketplace.

“Part of me sort of resents that there’s no filter,” he says. “There’s nobody saying, ‘Hey, over here is the best thing going in bilingual education,’ or ‘Over here is what you really want to have in your school to make science the best.’ ”

Atanasovska is one of the better ones, Waslawski says. Although there’s no independent research, she says there is some oversight of how she performs. The company sends someone to shadow her at work occasionally, and she files weekly progress reports to the school and company. In them, Atanasovska rates her own performance. “One, I see it in the student work,” she said. “I can see it in how the teachers are improving, and their teaching and practices have changed.”

Meanwhile, back in Australia, scores on the international test are declining. “The fascinating thing is that Australia is starting to drop,” said Snowball, who sold the company in 2007 and returned to Melbourne. “The basic teacher training isn’t as good here anymore.”

This article also appeared on the SchoolBook blog of The New York Times on June 22, 2012. Jill Barshay contributed reporting.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário